To a generation of Kenyans, the name ‘General Norman Schwarzkopf’ doesn’t ring a bell. He came long after Facebook, Twitter and mobile phones — before celebs started walking around half naked.

But there was a time when ‘Stormin’ Norman’, as the army general who commanded the United State’s attack against Iraq in 1991 was known, was a household name worldwide. His face was all over prime time television. Hailed as a brilliant military strategist, he was viewed, like Gen Collin Powel before him, as a future contender for the US presidency.

But when the old warrior, the liberator of Kuwait, passed on at the age of 77, he merited barely two inches of coverage buried deep inside local newspapers.

That is how fickle, how transient, fame is. One day you are the biggest thing in town, but barely a decade later, your neighbour’s children think you are just the old geezer next door. It is something politicians might want to remember as they fly from funeral to funeral emitting impotent thunder.

Kenyans are generally bored and idle. When you travel across the breath of the land, you notice distinguished citizens leaning on shop pillars and squatting next to squalid trenches in an advanced state of mental and physical rigor mortis — vegetating and doing nothing.

Their days are terribly long and empty. They scratch, sun themselves, yawn, belch and gossip but the hours still stretch before them. Occasionally, they get a little excitement — a grenade going kaboom, a matatu crushing, a thief getting lynched or a gangster getting shot 18 times in the head.

But such moments are not as common as one might imagine and they are spread too thinly on the ground. One could spend months, even years, leaning on a shop pillar without seeing anything of significance.

Once in a while, an enterprising corporate concern brings a road show. The whole shindig is recycled — from the loud music, the shrieking stereo, the stale comedian, the dancers wriggling stuffed up bottoms, a windy celebrity shouting themselves horse and cheap T-shirt, cheap cap, cheap phone and, very occasionally, a handful of wrinkled bank notes on offer. It is the sort of noise pollution the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) should ban. But to do so would be a crime against humanity, for what else would these bored souls do for entertainment, apart from getting ripped off by pata potea con artists and noisy street preachers?

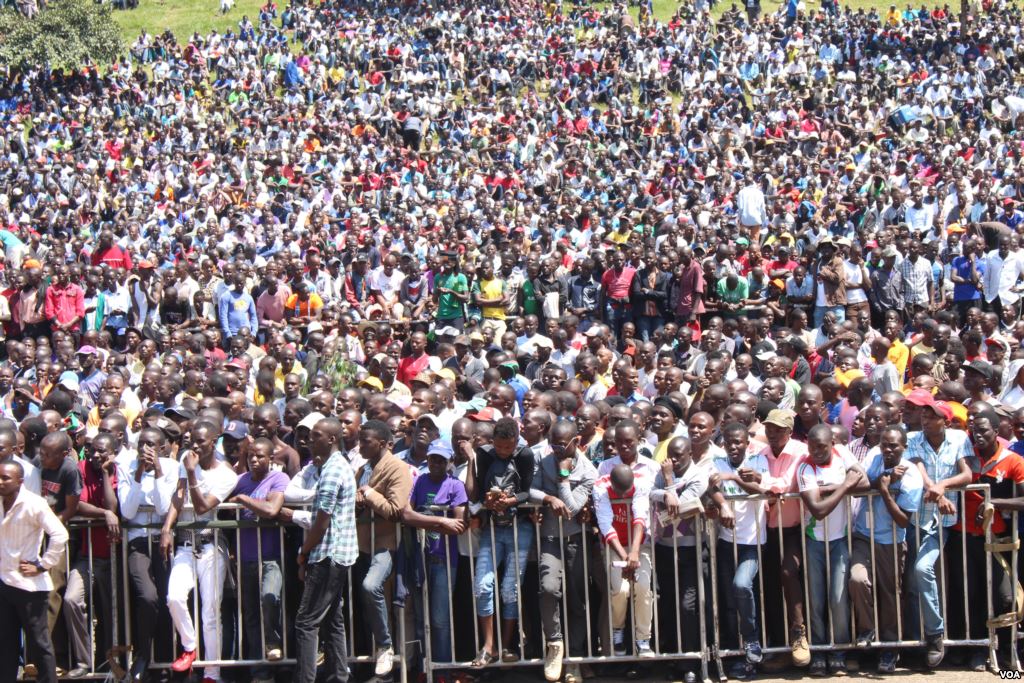

This is where the politician and his or her rally come in. Like moths to a light bulb, Kenyans congregate before a mad politician strictly for entertainment. In a sleepy hamlet where only the village tycoon owns a car — a rickety pick up that ferries produce and also doubles up as a hearse and an ambulance — a political rally is the biggest circus in town.

Potbellied men villagers only hear about come in the biggest cars ever seen, sometimes in choppers. It is a carnival: Loud music, acrobats, dances, bullfights. Which idle Kenyan would miss that?

They arrive and crane their necks. Others perch on treetops. They wait for hours, patiently, because for the whole lot of them, that rally is the only new thing they will see for eight boring months, apart from a neighbour’s goat giving birth to a five-legged kid. And even that is often just a rumour.

So a Jubilee politician sees this humongous mass of excited, cheering Kenyans in Kisumu and goes gaga. He elbows his mate in the ribs and, with a sly grin, whispers: “See how these guys love me! Tunawesmake, my brother!”

The opposition is not left behind. They travel to Kangema where ma elfu na ma elfu ya wananchi — to borrow a line once favoured by the national broadcaster — pour out to see the principals. They line up along roads. They come by boda boda, on foot — to see the great men with their own eyes; maybe even shake hands. “Wangapi wanakubiliana na sisi?” One of them asks. A sea of hands shoots up.

And so it goes, with politicians ejaculating off the massive crowd of ‘supporters’ who turn up everywhere to see them, forgetting that the mass of humanity is many times merely hungry for entertainment, or a freebie.

At least Norman Schwarzkopf, the old soldier never died — he just faded away. But in 12 months, when the politician who is today a warlord, a newsmaker and a kingmaker shuffles down the street, defeated, indebted and broken, even the goat idling on the tarmac won’t be bothered to lift an eyelid.